Before You Hire a Developmental Editor: What You Need to Know

/[Note: This blog post originally appeared on Jane Friedman’s website on December 15, 2022.]

In 2020, when I was heading the project to update the rates chart for the Editorial Freelancers Association (EFA), I asked our group of volunteers to update and define several editorial skills. If we were going to survey the membership about their rates, then our group, the membership, and potential clients all needed to have the same understanding of the editorial work in question.

Defining “copyediting” and “proofreading” was a straightforward task that sparked little debate. But when it came to “developmental editing,” it was nearly impossible to come to a consensus. Some saw developmental editing as a partnership between a writer and editor to “develop” a manuscript; others suggested that such an exchange of ideas would be considered “coaching” or “consulting.” Some insisted that “line editing” is a part of developmental editing; others were adamant that line editing is an entirely separate service. Most people in our volunteer group were not fans of the term “substantive editing” since all editing is, arguably, substantive.

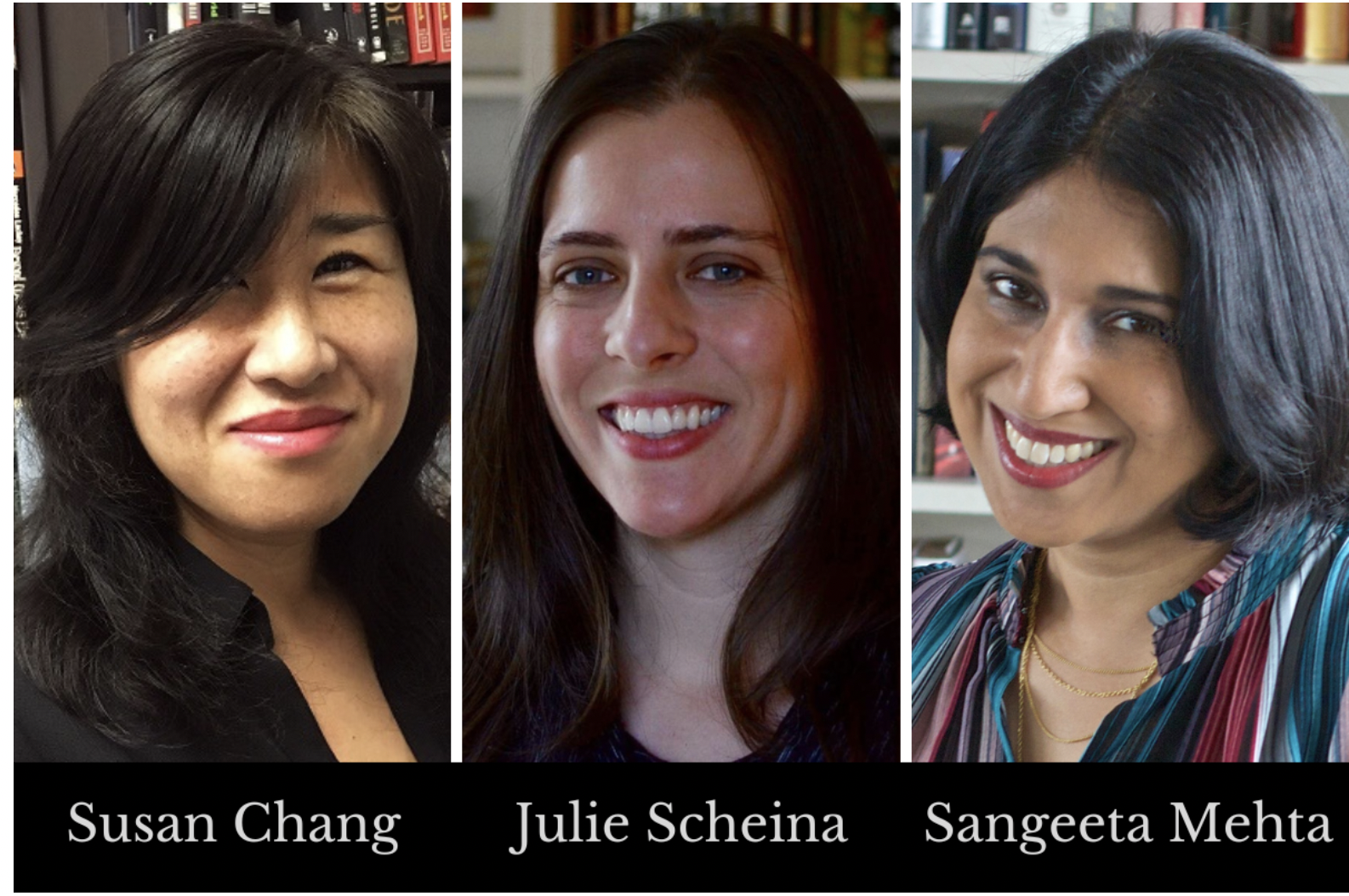

Two years later, I’ve continued to notice a wide range of approaches when it comes to freelance developmental editing. Those who specialize in trade books—or books targeted to a mainstream audience—also seem to have a different perspective from those who specialize in books for an academic or niche audience. To take a deep dive into the nuances of my focus, developmental editing of trade books, I spoke with longtime colleague Julie Scheina and new colleague Susan Chang, both of whom have similar training to me in that we have all worked for corporate trade book publishers. We differ, however, in terms of our specific work experience, years spent in the field, and genre interests. What follows is an edited version of our Zoom conversation.

To start, can you explain your definition of developmental editing? Is it the same or different from substantive, structural, comprehensive, and/or content editing? Where do editorial letters—better known in our field as “edit letters”—fit in? Are assessments, critiques, evaluations, and/or line edits part of your developmental editing services?

Julie Scheina: Funnily enough, it was only when I became a freelance editor that I heard the term “developmental editing.” When you work in-house for a publisher, different positions are assigned to each stage: there are editors who focus on acquisitions and developmental edits; copyeditors who focus on copyediting; and proofreaders who focus on proofreading. In the freelance world, it’s possible for one person to offer all of those services at different stages of the editorial process, and that’s where some of these confusing and overlapping terms come into play.

To me, developmental editing is any editorial feedback that helps the author strengthen and develop their manuscript between the initial draft and when the manuscript is ready for copyediting, proofreading, and publication. Different editors may call this substantive, structural, comprehensive, or content editing—to my knowledge they all mean basically the same thing.

The type of developmental editing that I provide for authors depends on the stage of the manuscript and the author’s needs. If the manuscript is in the earlier stages, I often provide a critique. This is a big-picture assessment of the manuscript’s core strengths and weaknesses. Usually critiques are shorter—around two or three pages—whereas a full editorial letter is typically longer and offers more specific feedback beyond those core areas.

I also offer line edits, depending on whether the manuscript is ready for that level of detail and if that’s how the author prefers to receive feedback. Some authors like to receive developmental line edits in earlier drafts, while others like to wait until their manuscript is further along.

Susan Chang: I had the same experience! I had never really used the term “developmental editing” before I got into freelancing. For me, it’s the same as global, structural, or content ending. And within that framework, I offer two different services: “manuscript assessments” and “developmental edits,” and the manuscript must be a completed draft. Any work prior to that stage I charge under my coaching rate. I have definitions on my website and on my rate sheet. If a writer has trouble deciding because they don’t understand the difference, I will share examples of a manuscript assessment and a developmental edit letter from clients who have given me permission to share these materials.

If we make an analogy to medicine, the assessment is the diagnosis. When I do an assessment of a manuscript, I diagnose the big global issues. The developmental edit is the prescription, so it deals with those issues in more depth, and I am offering suggestions for ways to fix the issues. This analogy to medicine might be pretentious—we’re not saving lives—but it comes from a task I was given when I started my career at HarperCollins Children’s Books: I was asked to transcribe a talk that legendary editor Ursula Nordstrom had given. She actually did say this—that, as an editor faced with a manuscript, you must take what amounts to the Hippocratic oath: First, Do No Harm. In the speech, Nordstrom pointed out that creative spirits can be harmed by careless, thoughtless comments. And as editors, we want to preserve that creative spirit.

Line editing is something that I will only do under special circumstances. If the writing is fairly strong and polished, and I think I can help bring it to another level, then I’m more apt to take it on. But if I’m needing to actually fix grammar and clarify meaning, then it’s too time-consuming and I won’t take it on.

Sangeeta Mehta: One reason I asked this question is that editorial organizations also vary in their definitions of “developmental editing.” While the EFA defines and offers classes on developmental editing, Editors Canada doesn’t name this skill as one of its four core editorial skills (though it does point out that the first of these skills, “structural editing” is also known as “developmental editing”). Since we tend to use medical terminology in our field, the reference to the Hippocratic Oath is fitting! For example, “book doctoring” is another common but ambiguous editorial specialization; some would call it heavy developmental editing while others would liken it to ghostwriting. All this is to say that writers should find out what exactly their developmental editor has in mind before hiring them.

For a writer seeking to improve their craft with the goal of landing a traditional trade book deal, how important is it to find a developmental editor who has worked in the field? Could an editor who has written or taught trade books, edited trade books on a freelance basis, or who closely follows industry news be just as effective as someone who has been in the trenches, so to speak?

SC: You don’t necessarily need to have worked in traditional publishing to be able to help an author improve their story. When I was starting my business, I asked a good friend, an author and a writing coach who leads retreats, and who has never worked in traditional publishing, to show me an example of one her editorial letters, and it was honestly one of the most impressive editorial letters I’ve ever read. She was amazing in terms of the craft.

That said, what an editor with in-house experience can offer you, that is not going to come from anyone who has not been in the industry, is the marketing sensibility about what is commercial. We have an instinct for if a book is going to be commercial enough for traditional publishing because it’s been beaten into us as (acquiring) editors. You need a hook and a target market, and this needs to be articulated to everyone you’re pitching the book to, from agents all the way down the line to the end consumer, the reader. So, if your goal is to be traditionally published, then you might prefer someone with this kind of insider knowledge.

JS: I think that the type of experience someone has is more important than where they got that experience. There are many teachers and authors who have a wealth of experience providing constructive editorial feedback. At the same time, being an experienced author or teacher doesn’t automatically equate to being an experienced editor. Each role requires different skill sets. Effective editorial feedback is specific as well as actionable. An editor should not just be able to identify a weak character arc, for example, but also give the author suggestions for how to strengthen that character.

Personally, I do feel that working in-house at a large traditional publisher gave me a valuable depth and breadth of experience. Editors who have worked in-house can often provide insight into publishing’s many confusing and complicated processes. But I would never say that an editor who hasn’t worked in-house can’t help writers improve their craft, because I’ve seen many examples to the contrary.

SM: While some of the best editors I know are educators and authors or are self-taught, I agree that those who have worked in publishing house—large or small, corporate or independent—are more likely to think critically about how books fit into the marketplace. (Freelance editors who have previously worked as literary agents are even better trained in this kind of thinking, but if they are actively agenting at the same time they are running an editing business, they should abide by the Association of American Literary Agents’ canon of ethics to avoid a potential conflict of interest.) If I don’t consider the premise and competition when I’m editing, then I find myself working at the sentence or paragraph level rather than holistically. However, I imagine that authors at the beginning stages of their careers or who are open to self-publishing might be happier with someone who prioritizes craft over market concerns.

On this same note, how important is it for the editor to have experience in the writer’s genre and category? For example, do you think that a former acquiring editor of adult novels can effectively edit teen novels? What about someone who has years of experience at a mystery or romance imprint? Should a writer trust this editor with their work of nonfiction—children’s or adult?

JS: Many genres and age groups do overlap, though there are some important distinctions between certain categories. I’ll use myself as an example. My focus is solely on fiction, and one piece of advice I give to authors is to finish their full manuscript and revise it before they begin querying. However, the process for nonfiction is very different. Nonfiction is often sold on a proposal, some sample chapters, and a table of contents or an outline. Because I don’t edit nonfiction, my advice and experience wouldn’t be as helpful or applicable.

Likewise, readers of certain genres may have specific expectations or tropes, such as a “happily ever after” in romance. Editors generally need to have a foundational knowledge of typical tropes in the genres they edit, even when an author is working to subvert readers’ expectations.

When it comes to age group distinctions, there’s definitely more overlap between young adult thrillers and adult thrillers than between young adult thrillers and adult nonfiction. Sometimes an author may not be sure whether their book is a better fit for middle grade versus young adult readers, for example, or for young adult versus adult. In these cases, an experienced editor can help authors to position their book for the right market.

If an editor doesn’t usually edit a certain category or genre, I’d advise authors to consider the specific type of feedback they are seeking and whether the editor’s experience is a good match. For example, I’ve had authors who’ve said, “I know you don’t usually edit adult fiction, but I’d like your thoughts on this character arc because your character development notes on my young adult book were helpful.”

SC: I have a lot of thoughts here. I always say that in terms of genre, the children’s book people are generalists and adult editors are specialists. What children’s book editors do have specialized knowledge about is their target audiences. There are certain nuances of editing for specific age ranges that we have internalized that editors who have only worked on adult books might not be aware of. Fewer adult professionals read or are familiar with children’s or YA books. Whereas children’s book editors are adults, and we read adult books all the time!

Generally, I think that anyone with a good sense of storytelling and craft can edit anything, but for children’s and young adult books, there has to be a genuine sensibility for the specific audience.

SM: Sometimes one’s specialization depends on where in the field they land. For example, I’ve worked at companies that specialize in literary fiction, business books, and children’s books because these are the jobs that have come my way, so I have applied some of these experiences to my editing business. None of my past employers have focused on commercial fiction for adults, but I actively take on such projects because I tend to read in this area more than in others. Writers might ask the editor they are considering hiring about their reading interests and tastes, if the editor doesn’t have demonstrated experience in the writer’s genre, age category, or literary form.

Most independent developmental editors base their fees on their past work experience. This means that a former SVP at Random House who had a hand in publishing international bestsellers, for instance, is likely to charge a higher—in some cases, exorbitant—fee as compared to an editor who acquired for a lesser-known house and didn’t climb the corporate ladder. But is the writer necessarily getting a better editor? Better industry contacts, assuming the editor chooses to share them?

SC: I don’t think that the level an editor reached in the industry correlates to how much they can charge–I definitely didn’t take that into consideration when setting my rates. But if any editor or former SVP can convince clients to give them exorbitant fees because they got higher up on the ladder, more power to them.

Clients aren’t necessarily getting a better editor, because, as I mentioned earlier, I know amazing editors who have never worked at a publisher. Nor do I think that sharing industry contacts is or can ever be part of the service. If I believe in a project, and if I genuinely believe I can help the client get to the next stage, whether that is finding an agent or suggesting that their agent share it with certain editors, I will share contacts. But I don’t know that when I’m signing them, so that never comes into the computation of the fee.

JS: In publishing, you’re often given more managerial responsibilities as you rise higher on the ladder, so you’re not necessarily editing more than you were before; you may be editing fewer, higher-profile books and managing other editors, for example. That’s one of the reasons that I love freelancing—it allows me to focus fully on editing rather than juggling the other responsibilities of an in-house editor.

Editors with higher titles and who worked on higher-profile books are likely more visible, which means they may be more in demand and able to charge higher fees. However, while a title can show how valued an editor was at their publishing house, I don’t think that title alone is always an accurate barometer of editorial skill. I’d place greater value on an editor’s years of experience working on specific books in an author’s category and genre. Personally, I feel like I’m always learning as an editor. Every author I work with and every book I work on teaches me something new, and I’m able to pass that on to the next author I work with.

In terms of industry contacts, I enjoy helping authors with their query letters and answering questions about the submissions process. But I advise authors that it’s in their best interests to research agents themselves, even though it’s a time-consuming process. Researching agents allows authors to get a better sense of whether they connect with an agent’s communication style, if the agent’s advice resonates with them, and generally whether the agent might be a good fit for them and their work.

SM: We’ve all had a hand in editing bestselling books, communicating with famous authors, and making deals with powerful literary agents. When working for a corporate publisher, this comes with the territory. But I agree that this experience doesn’t correlate with an editor’s ability to edit. Acquiring books and shepherding them through the publishing process is a different skill from developmental editing. If an author hires an editor based solely on the editor’s portfolio and the allure of contacts it could lead to, it’s possible, but not likely, that their expectations will be met.

At what point in their career do you recommend that a writer hire a developmental editor? At the idea or outline stage? Once they’ve completed a draft? Or once they have taken their draft as far as they can, after incorporating feedback from beta readers and/or critique partners?

JS: Ideally, I encourage authors to try to take their manuscript as far as they can on their own before they pay for professional feedback, particularly if they are budget conscious or if they’re relatively new to writing books. This may mean making connections with critique partners, writing groups, or other trusted readers who can share initial feedback, or even just putting the manuscript away for a few weeks and then rereading and revising it. These steps can help authors identify issues that may be readily apparent and can allow the professional editor to share feedback that’s more specific and nuanced than it would be with an initial draft. Forming strong connections within the writing community can also be invaluable for authors over the course of their career.

While this approach is more cost-effective than hiring an editor for every pass, of course the trade-off is time. Not everyone has access to trusted readers or the time to form those connections before moving forward with their manuscript. Likewise, some authors find it helpful to get professional feedback on an outline or on multiple story ideas before moving forward. So there isn’t one perfect time or one best way to approach the process—it depends on authors’ needs, budget, and schedule.

SC: It’s definitely based on how much budget you have. If you have a finished draft that is very raw, and you can afford to pay for multiple rounds of developmental editing, that’s great. But if you can only afford one round of developmental editing, then definitely get your draft as far as possible yourself before you hire that editor. It will save you time.

You might work with a bunch of beta readers or with a critique group, but when you’re ready for a professional read, you will probably be shocked at how much more you’re going to get from the professional. There’s a difference in the quality of feedback. A professional editor is not your friend. They’re not trying to spare your feelings. They will approach the criticism with honesty–and hopefully with some tact and compassion, which is how I always try to do it.

That being said, I do offer editorial coaching at an hourly rate to take ideas from concept to synopsis to outline to first draft. For example, I’m working with a client now: I asked him to give me twenty-five ideas, one sentence each. One of them is a slam-dunk to pitch as a series, so we worked on outlines for the first two books. He’s writing drafts and then I’m going to help him put together a series proposal.

SM: I feel that I’m most helpful when working either on a completed draft or on the first several chapters of a novel plus a synopsis or outline. But yes, a writer can find that it’s just as or more effective to work with an editor at an earlier stage of the writing process. In some cases, the editor might function as more of a sounding board or accountability partner than as a developmental editor. But again, this skill is open to interpretation, and such support might be exactly what the writer needs to develop their manuscript.

Many copyeditors, especially those who are new to freelancing, offer a free sample edit to help potential clients make an informed hiring decision. Should writers expect the same of developmental editors? Request references or speak with them on the phone? Do you think it’s best for writers to go with an editor who offers written feedback, or can oral feedback be just as valuable when it comes to developmental editing?

SC: I never do sample edits, because I don’t think you can do a sample edit for a global process like developmental editing or even a manuscript assessment, but I will provide examples of previous work if asked. What I offer instead is to read a potential client’s query package and then set up a free consultation to give them my preliminary thoughts based on the sample.

I always provide written feedback, but some of my coaching clients seem to prefer to discuss my feedback in addition, or like to brainstorm over Zoom, so I’m happy to set up weekly or biweekly brainstorming sessions. I’m pretty flexible because I enjoy working in all different ways, and I tailor the approach to each client, because different writers process feedback in different ways.

JS: Developmental editing is different from copyediting in this way, because it requires an understanding of how the characters and story progress over the course of the full manuscript. To me, providing a sample developmental edit on ten pages of a full-length novel would be like writing a restaurant review after taking one bite of an appetizer—it’s not really feasible or helpful.

While I don’t provide sample developmental edits, I often talk to authors beforehand so that they can ask questions and get a sense of my approach as well as the overall process. That personal connection can be helpful when authors are making the difficult decision of who to entrust with their work, which is not something I take lightly.

In terms of feedback, I always make written notes as part of my editorial process. I’m a visual learner, and writing helps me to organize my thoughts and to be more specific and concise. So I almost always provide written notes, and then the author and I will set up a time to talk after they’ve had a chance to review them. Phone calls work well for follow-up questions because we can have more of a dialogue, or even a spontaneous brainstorming session. I also think that written notes are helpful because an author can return to them during the revision process, rather than trying to remember a conversation that may have happened weeks or months ago.

SM: I don’t know of any experienced developmental editors (those who have been in the industry for at least a few years) who offer sample edits. Most provide written comments in the form of an editorial letter. I’ve heard of editors delivering feedback on the phone without offering any written notes—but writers should keep in mind that this makes it easy for the editor to tell them what they want to hear without doing a deep analysis. I’ve also found that some writers are loath to interact with an editor on the phone but will gladly email or chat on an app. This is another reason writers should ask themselves what kind of feedback they prefer—casual or concrete.

We all know how subjective this industry is. One literary agent’s or acquiring editor’s taste can be vastly different from that of another. It’s no wonder we often hear the phrase, “it only takes one yes!” We also all have our individual tastes. That said, do you sometimes encourage writers to consult with different developmental editors before they delve into revisions?

JS: My view is that the earlier someone is in the writing process, the more people they can consult with for feedback. So if an author has an initial idea or wants to talk about a particular part of their book, for example, then they might run it by their writing group. As authors move forward with their manuscript, I recommend they narrow the amount of feedback they solicit until they are ultimately sharing their polished draft with only one or two trusted readers. Books are subjective, and it’s common for editors to give conflicting notes about the same manuscript. If authors try to incorporate feedback from too many different sources, their original voice and vision can start to become lost.

The subjective nature of editing is also one of the reasons why I always ask authors to share the first 10–15 pages of their manuscript with me, along with a plot summary and any other details about the project and their goals for working with an editor. If I don’t have a clear vision for how I can help the author strengthen their manuscript, then I’ll recommend that they consider reaching out to other editors. I’ve also advised authors who’ve completed a particularly significant or challenging revision to share the manuscript with a trusted fresh reader—someone who hasn’t read the previous drafts—in order to get a sense of whether the changes they’ve made are working effectively.

SC: I’m happy to recommend other editors if I’m not able to take a project on, either because I don’t have time or I don’t resonate with it. But I never recommend that they get multiple edits of the same pass because I think it’s counterproductive. You have to develop your own gut sense of what’s right for your own work in the end. Even when I was in-house, I always made sure to tell my authors: it’s your name on the book, so you always have final say.

And on this side of the desk, I always thank people for trusting me with their books, because it is a huge deal. But if you trust me with your book, then you kind of have to trust my feedback, assuming that it feels right to you; and if you’re listening to feedback from five other editors you’ve hired, and you have this sense of insecurity or paralysis, and you haven’t yet developed that author gut, then you’re not going to get anywhere.

SM: Admittedly, I sometimes encourage writers to seek feedback from other developmental editors. In the same way a patient might seek a second opinion from a doctor, a writer might want a second opinion from a reputable editor, especially if the first editor’s opinion isn’t sitting well with them. I’m flattered when writers ask me my opinion, but they should always trust themselves.

Are there any red flags writers should look out for in their search for an independent editor, perhaps an editor who subcontracts without informing their clients? Or for whom freelancing is a stopgap between salaried positions? After all, anyone can hang up their editor shingle, and none of us can promise our clients an agent or book deal. What are writers paying for, besides an opinion?

SC: I think that the biggest red flag is somebody with suspiciously low rates—so someone, for example, who will do a developmental edit on an 80,000-word manuscript for $500. Another red flag is an editor who doesn’t approach this job in a professional way. They should communicate with you in a reasonable timeframe; deliver their edits on time, and give you a professional level of feedback.

If the editor subcontracts and they tell you, and you’re okay with this, then it’s fine. If the editor is freelancing as a stop gap, then they have to finish their work with you no matter what.

A written agreement is also important because it validates the editor as a professional. It should spell out what that service is, when it’s due, what happens if the editor doesn’t deliver, payment terms, etc. Both parties have to protect themselves.

JS: It’s a red flag if an editor is reluctant to put the project terms in writing. I always share a written agreement that outlines the details the author and I have discussed, including the manuscript length, the type of editorial notes, the fee, and the delivery and payment schedules.

If you’re working with an editorial consulting group rather than with an individual editor, you should know which specific editor you’ll be working with before you move forward.

Lastly, editing is a skill that is honed with time and practice. Before you invest in working with a professional editor, take the time to research the editor’s experience. What’s their online presence like? Do they share other books they’ve edited, testimonials from other authors they’ve worked with, or other details about their experience? I believe it’s important for authors to find an editor who they trust—not only to identify the weaknesses of their book, but who has the necessary expertise to thoughtfully guide them in strengthening those weaknesses.

SM: Another red flag could be unusually high rates, especially from an editor who is just starting out. And yes, a written agreement or statement—but not necessarily a contract—is a must. I’ve heard of “handshake” deals between agents and writers, and this often leads to disappointment for the author. If an author is hiring a freelance editor, the terms should be very clear since a fee is involved.

Do you have any other advice for writers looking to hire a freelance developmental editor of trade books?

JS: Think carefully about what you hope to achieve by working with a freelance editor. In addition to the financial investment, do you currently have the time and creative energy to think deeply about your book and to complete revisions that may be challenging? How do you prefer to receive feedback? Do you connect with what you can see of the editor’s communication style?

Many freelance editors’ schedules become booked a few months in advance. When possible, authors should begin researching and reaching out to potential freelance editors in advance of when they’d like to start working together.

SC: Ask around for personal recommendations like you do when you’re hiring any professional, like an accountant or a lawyer. Do your due diligence, read testimonials and reviews, and definitely talk to the editor first. You’re entrusting that person with your hopes and your dreams and potentially years of your life. Traditional publishing is a small world. It’s based on relationships, reputation, and trust. And if your end goal is to be traditionally published, it’s on you to do your research, whether you’re looking for a freelance developmental editor to get your manuscript into the best possible shape to land an agent, acquisitions editors to add to your wish list, or your dream publishing houses to submit to. Good luck!

Julie Scheina is the owner of Julie Scheina Editorial Services, LLC, and a former senior editor at Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. Julie has over fifteen years of experience editing acclaimed and bestselling books for children and young adults. She has edited more than 200 titles across a variety of genres, from picture books and poetry collections to middle grade and young adult novels, and she brings this depth of experience and industry knowledge to every project. Books that Julie has edited have spent more than 125 combined weeks on the New York Times bestseller list and include #1 New York Times bestsellers, a Lambda Literary Award finalist, a William C. Morris Young Adult Debut Award finalist, an Andre Norton Award for Young Adult Science Fiction and Fantasy nominee, an Edgar Award nominee, Bram Stoker Award nominees, and a New York Times Best Illustrated Children’s Book. Julie also has a free resource for writers, Your Editor Friend, a series of weekly letters filled with writing guidance, revision advice, and encouragement.

Susan Chang is a freelance developmental editor with thirty years of experience acquiring books at Big Five publishers. She began her publishing career at HarperCollins Children’s Books, where she worked for nine years before moving on to shorter stints at Hyperion Books for Children (a former imprint of Disney Publishing Worldwide) and Parachute Publishing, a book packager. She was a senior editor at Tor Books (Macmillan Publishers) for seventeen years before launching Susan Chang Editorial. She lives in Queens, the most diverse borough of New York City. Learn more at susanchangeditorial.com.

Sangeeta Mehta (Mehta Book Editing) has worked in the book publishing field since the late 1990s. She has been an acquiring editor at both Little, Brown Books for Young Readers (the children’s division of the Hachette Book Group) and Simon Pulse (the teen paperback division of Simon & Schuster). At Little, Brown, she worked with debut authors and some of the most prominent names in publishing. At Simon Pulse, she acquired and edited commercial fiction and non-fiction and ran two paperback series. She later returned to Hachette to freelance-edit an international bestseller. Prior to working in New York publishing, Sangeeta was a projects manager/reader for West Coast literary agents Margret McBride and Charlotte Gusay. For six years, she served on the Board of Governors of the Editorial Freelancers Association, where she launched and chaired the organization’s Diversity Initiative. She has also served on the board of The Word: A Storytelling Sanctuary.